These are my notes from Freya Holmér's excellent presentation from Dutch Game Day 2023.

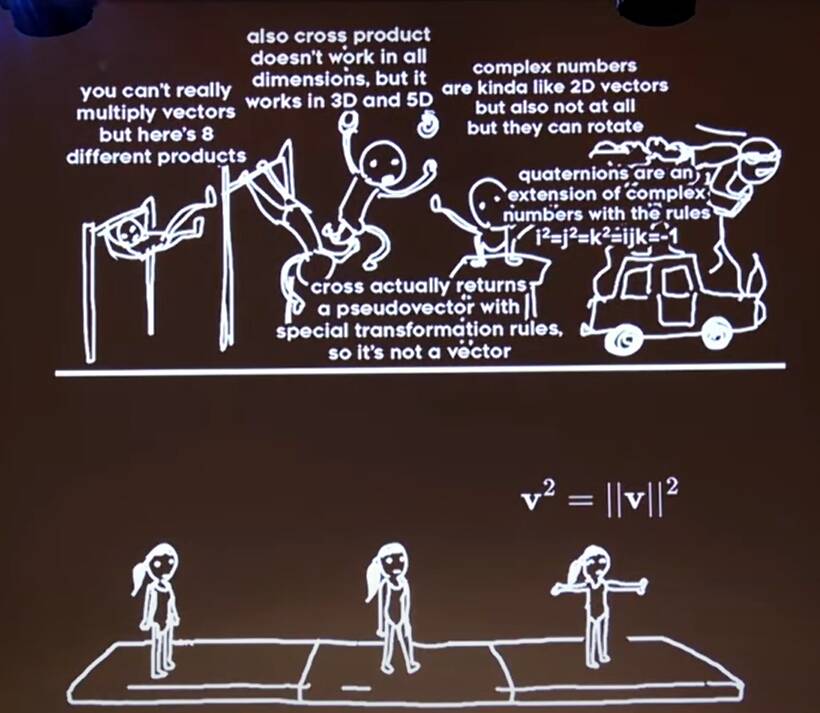

Why Can't We Multiply Vectors

Let's start with the requirement that \[ \mathbf{v}^2=\left\|\mathbf{v}^2\right\| \] For example \[ (1,2,3)^2 = 1^2+2^2+3^2 = 14 \]

What about our basis vectors

\[

\begin{align*}

\mathbf{x}\mathbf{x} &= \mathbf{x}^2 = 1^2 = 1\\

\mathbf{y}\mathbf{y} &= \mathbf{y}^2 = 1^2 = 1\\

\mathbf{z}\mathbf{z} &= \mathbf{z}^2 = 1^2 = 1

\end{align*}

\]

\[

\begin{align*}

\mathbf{x}\mathbf{x} &= \mathbf{x}^2 = 1^2 = 1\\

\mathbf{y}\mathbf{y} &= \mathbf{y}^2 = 1^2 = 1\\

\mathbf{z}\mathbf{z} &= \mathbf{z}^2 = 1^2 = 1

\end{align*}

\]

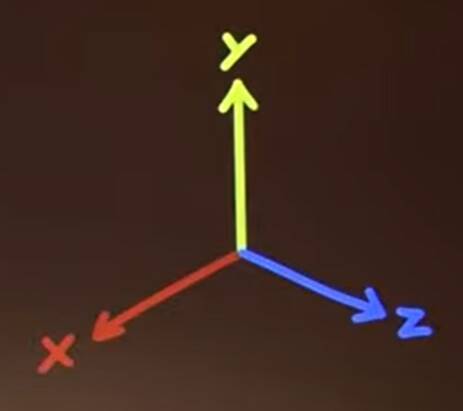

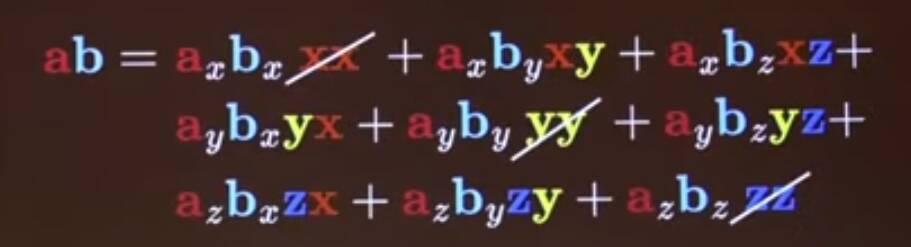

Expanding the product

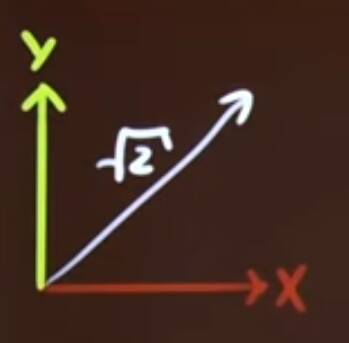

Writing \(\mathbf{a}=a_x\mathbf{x} + a_y\mathbf{y} + a_z\mathbf{z}\), and naively expanding: \[ \begin{align*} \mathbf{ab} &= a_xb_x\mathbf{x}\mathbf{x} + a_xb_y\mathbf{x}\mathbf{y} + a_xb_z\mathbf{x}\mathbf{z} \\ &+ a_yb_x\mathbf{y}\mathbf{x} + a_yb_y\mathbf{y}\mathbf{y} + a_yb_z\mathbf{y}\mathbf{z} \\ &+ a_zb_x\mathbf{z}\mathbf{x} + a_zb_y\mathbf{z}\mathbf{y} + a_zb_z\mathbf{z}\mathbf{z} \end{align*} \] and then \(\mathbf{x}\mathbf{x} = 1\), so this simplifies to \[ \begin{align*} \mathbf{ab} &= a_xb_x + a_xb_y\mathbf{x}\mathbf{y} + a_xb_z\mathbf{x}\mathbf{z} \\ &+ a_yb_x\mathbf{y}\mathbf{x} + a_yb_y + a_yb_z\mathbf{y}\mathbf{z} \\ &+ a_zb_x\mathbf{z}\mathbf{x} + a_zb_y\mathbf{z}\mathbf{y} + a_zb_z \end{align*} \] So collecting the scalars \[ \begin{align*} \mathbf{ab} &= a_xb_x + a_yb_y + a_zb_z &+ a_xb_y\mathbf{x}\mathbf{y} + a_xb_z\mathbf{x}\mathbf{z} \\ &+ a_yb_x\mathbf{y}\mathbf{x} + a_yb_z\mathbf{y}\mathbf{z} \\ &+ a_zb_x\mathbf{z}\mathbf{x} + a_zb_y\mathbf{z}\mathbf{y} \end{align*} \] So what are \(\mathbf{x}\mathbf{z}\) etc.? Consider the diagonal between \(\mathbf{x}\) and \(\mathbf{y}\):

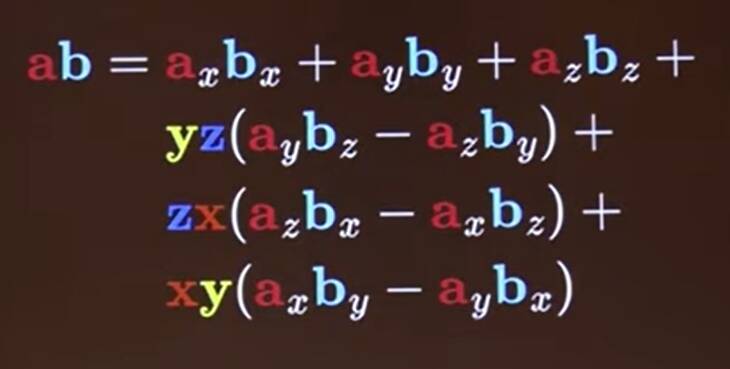

It's length is \(\left\|\mathbf{x}+\mathbf{y}\right\|=\sqrt{2}\). But then we can square it, using \(\mathbf{v}^2=\left\|\mathbf{v}\right\|^2\), \[ \begin{align*} (\mathbf{x}+\mathbf{y})^2 &= \mathbf{x}\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{x}\mathbf{y} + \mathbf{y}\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{y}\mathbf{y} \\ &= 1 + \mathbf{x}\mathbf{y} + \mathbf{y}\mathbf{x} + 1 = 2 \end{align*} \] and so \[ \mathbf{x}\mathbf{y} + \mathbf{y}\mathbf{x} = 0 \] or \[ \mathbf{x}\mathbf{y} = -\mathbf{y}\mathbf{x} \] So we get

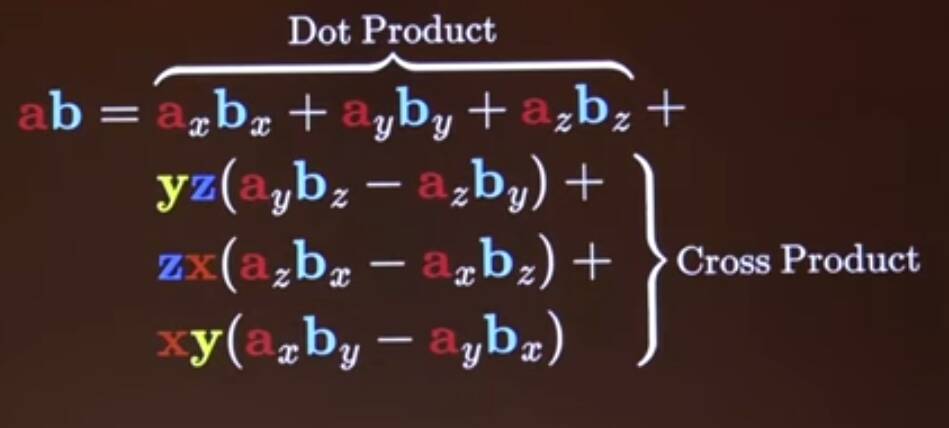

And we recognise the dot and cross products

And then

\[(\mathbf{x}\mathbf{y})^2=\mathbf{x}\mathbf{y}\mathbf{x}\mathbf{y}=-\mathbf{x}\mathbf{x}\mathbf{y}\mathbf{y}=-1\cdot 1=-1\]

And thus

\[(\mathbf{x}\mathbf{y})^2=(\mathbf{y}\mathbf{z})^2=(\mathbf{z}\mathbf{x})^2=(\mathbf{x}\mathbf{y})(\mathbf{y}\mathbf{z})(\mathbf{z}\mathbf{x})=-1\]

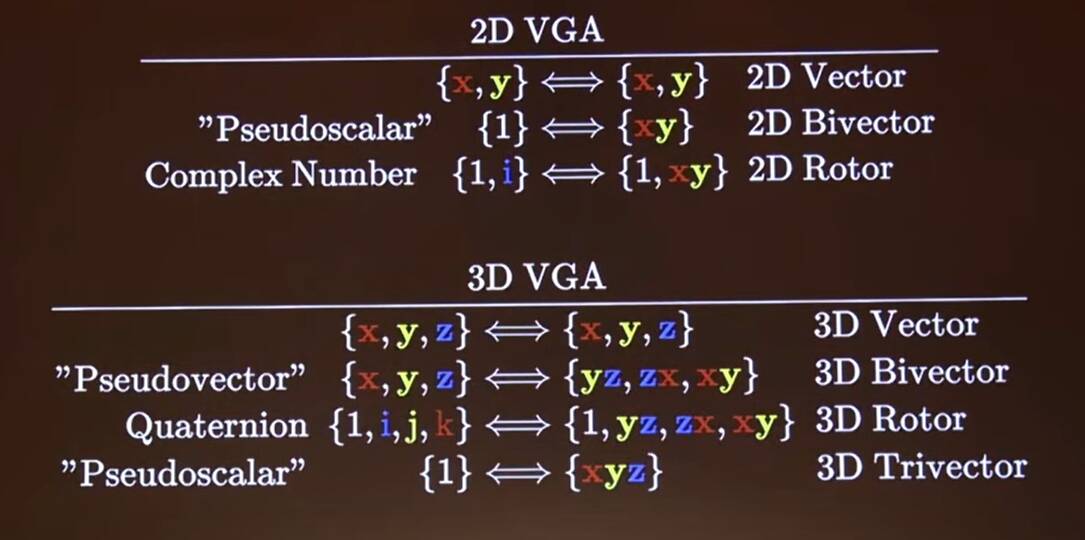

And this is familiar, the quaternions:

\[i^2=j^2=k^2=ijk=-1\]

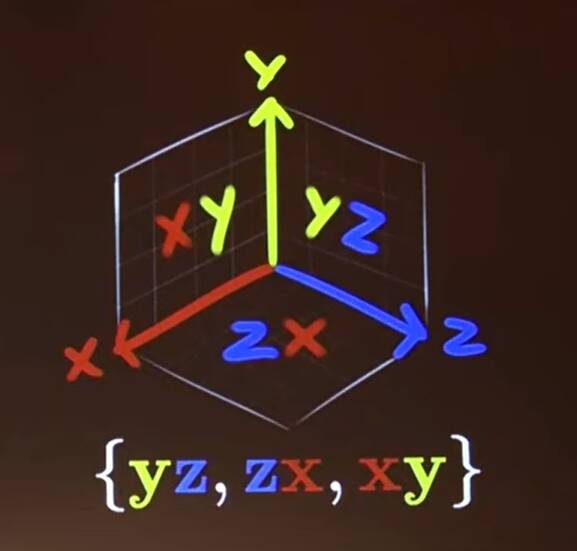

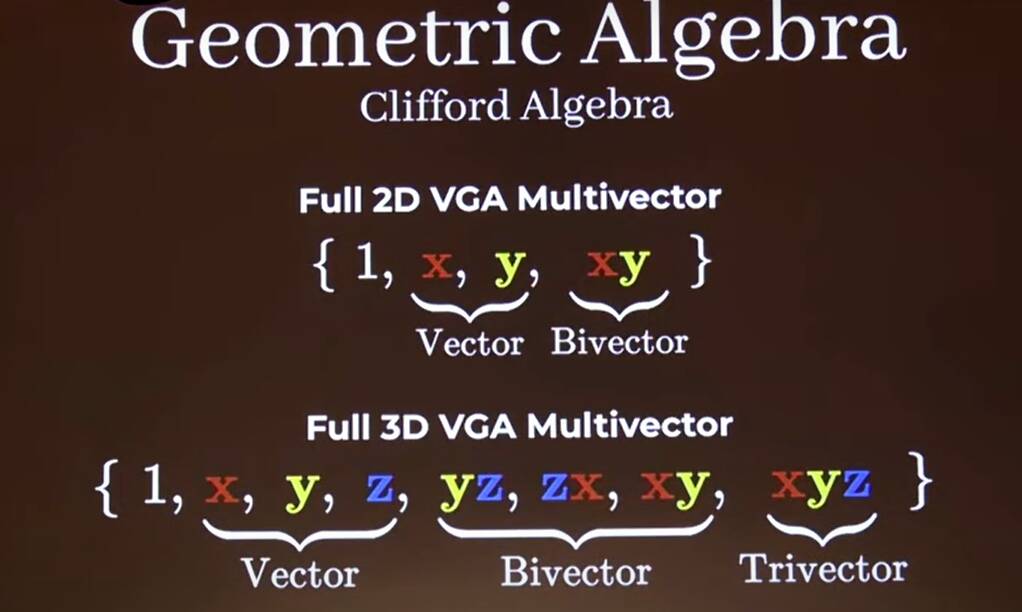

So our vector products live in a space with basis

\[\left\{1,\mathbf{x}\mathbf{y},\mathbf{y}\mathbf{z},\mathbf{z}\mathbf{x}\right\}\]

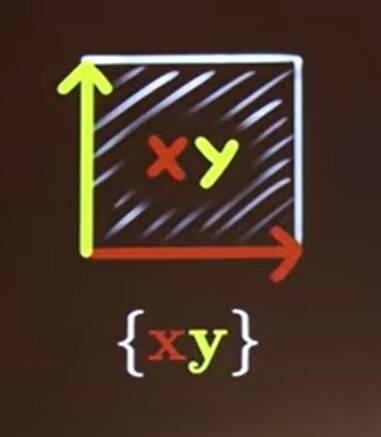

What about 2D?

We get

\[\mathbf{ab} = a_xb_x + a_yb_y + \mathbf{xy}(a_xb_y - a_yb_x)\]

which has a basis of

\[\left\{1,\mathbf{xy}\right\}\]

with

\[\mathbf{xy}^2=-1\]

which looks like the complex numbers.

Planes and Clifford Algebras

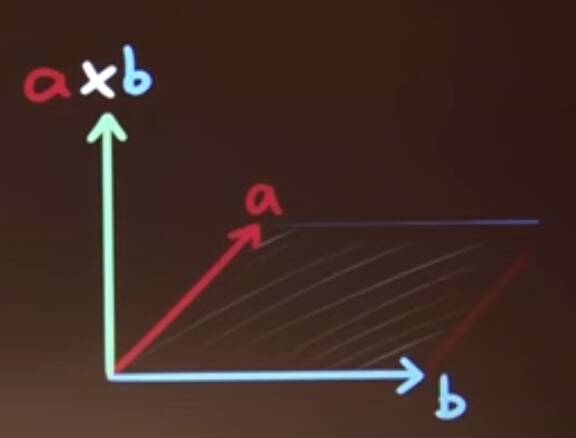

Now the cross product has magnitude equal to the area of the parallelogram constructed from the two vectors, and is in a direction perpendicular to them. So maybe this has something to do with planes.

Now we call \(\mathbf{xy}\) a bivector (whereas \(\mathbf{x}\) is a vector). And we consider basis bivectors:

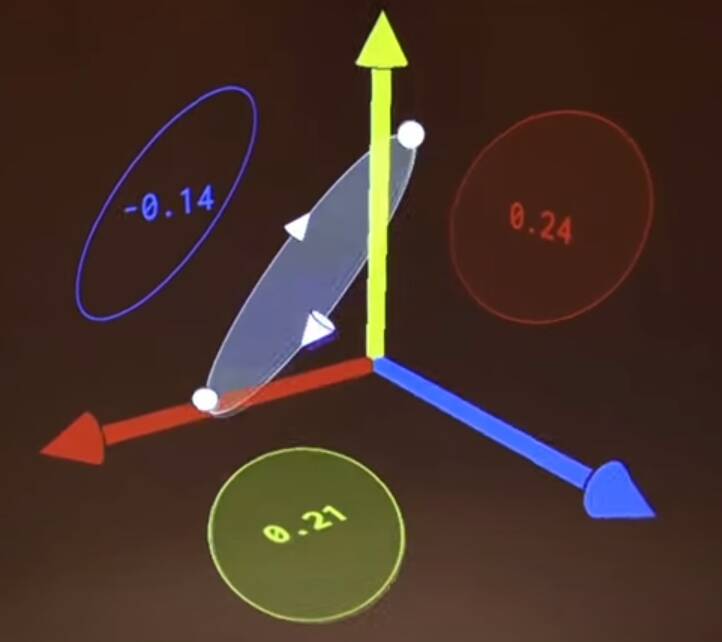

But maybe rather than as a vector, we can treat the product as an oriented area:

It is specified by three components, e.g. \((0.1,0.2,0.3)\), like a vector, but algebraically behaves differently since it is has a basis of \(\{\mathbf{xy},\mathbf{yz},\mathbf{zx}\}\).

Bivectors represent the minimum information required in any given dimension, to store both a plane and a magnitude. These show up in rotations because rotations happen in a plane. Rotations happen in a plane, rather than around an axis. (In 2D, for example, there is no axis, merely a centre point.)

Looking Back At The Cross Product

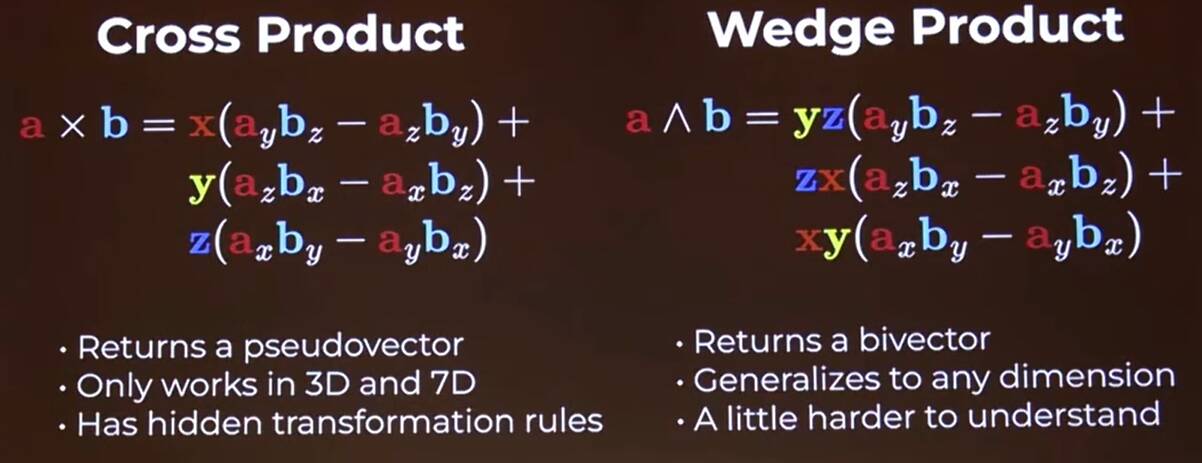

The cross product is a pseudovector, only works in 3D and 7D, and behaves differently to vectors under reflection of the axes. Whereas there is the wedge product has the same components but different basis vectors:

So we get

that is:

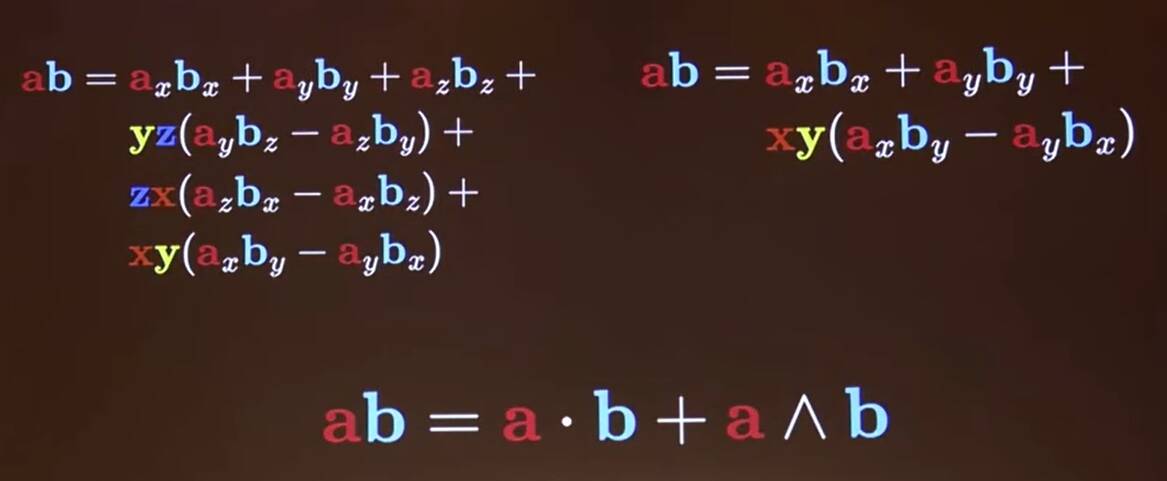

\[\mathbf{ab}=\mathbf{a}\cdot\mathbf{b}+\mathbf{a}\wedge\mathbf{b}\]

The product of two vectors is the sum of the dot product and the wedge product.

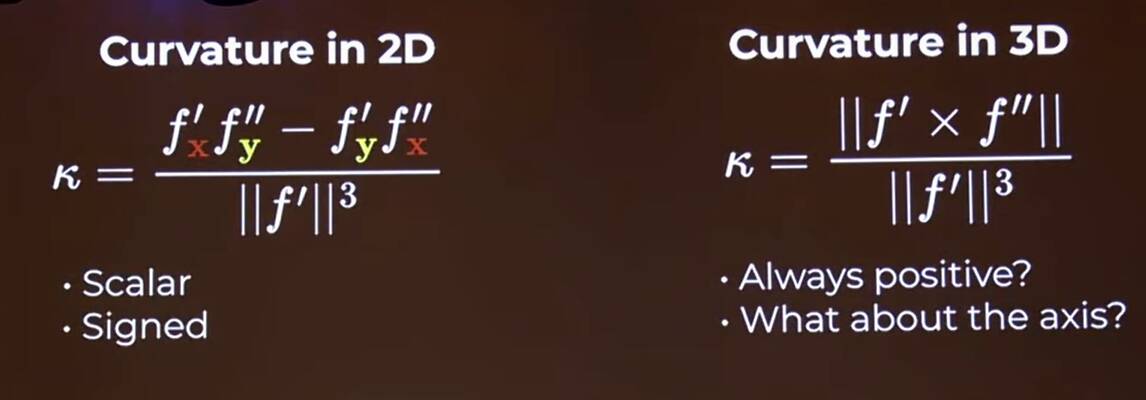

Example: Curvature

Actually we have

\[\kappa = \frac{f^{\prime}\wedge f^{\prime\prime}}{\left\|f^\prime\right\|^3}\]

which generalises to any dimension. In the case of the 2D curvature, the sign comes out of the wedge product.

Summing up

So rather than the messy situation we had before, now everything follows from the axiom that \[\mathbf{v}^2=\left\|\mathbf{v}\right\|^2\]

Geometric Algebras

What does Multiplication Represent

The product is:

- a rotation by twice the angle between the two vectors (where angle is \(0\leq\theta<\pi\)),

- in the plane containing those two vectors

- with the direction of rotation going from the first (left) vector to the second (right)